Draft

This page is not complete.

Sending data is not enough — we also need to make sure that the data users fill out in forms is in the correct format we need to process it successfully, and that it won't break our applications. We also want to help our users to fill out our forms correctly and don't get frustrated when trying to use our apps. Form validation helps us achieve these goals — this article tells you what you need to know.

| Prerequisites: | Computer literacy, a reasonable understanding of HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. |

|---|---|

| Objective: | To understand what form validation is, why it's important, and how to implement it. |

What is form validation?

Go to any popular site with a registration form, and you will notice that they give you feedback when you don't enter your data in the format they are expecting. You'll get messages like:

- "This field is required" (you can't leave this field blank)

- "Please enter your phone number in the format xxx-xxxx" (it wants three numbers followed by a dash, followed by four numbers)

- "Please enter a valid e-mail address" (the thing you've entered doesn't look like a valid e-mail address)

- "Your password needs to be between 8 and 30 characters long, and contain one uppercase letter, one symbol, and a number" (seriously?)

This is called form validation — when you enter data the web application checks it to see if it is correct. If so, it allows it to be submitted to the server and (usually) saved in a database; if not, it gives you error messages to explain what you've done wrong (provided you've done it right). form validation can be implemented in a number of different ways.

The truth is that none of us like filling in forms — there is a lot of evidence to show that users get annoyed by forms, and are one of main things that will cause them to leave and go somewhere else if they are done badly. In short, forms suck.

We want to make filling out web forms as non-horrible as possible, so why do we insist on blocking our users at every turn? There are three main reasons:

- We want to get the right data, in the right format — our applications won't work properly if our user's data is stored in any old format they like, or if they don't enter the correct information in the correct places, or omit it altogether.

- We want to protect our users — if they entered really easy passwords, or no password at all, then malicious users could easily get into their accounts and steal their data.

- We want to protect ourselves — there are many ways that malicious users can misuse unprotected forms to damage the application they are part of (see Website security).

Different types of form validation

There are different types of form validation that you'll encounter on the web:

- Client-side validation is validation that occurs in the browser, before the data has been submitted to the server. This is more user-friendly than server-side validation as it gives an instant response. This can be further subdivided:

- JavaScript validation is coded using JavaScript. It is completely customizable.

- Built in form validation is done with HTML5 form validation features, and generally doesn't require JavaScript. This has better preformance, but it is not as customizable.

- Server-side validation is validation that occurs on the server, after the data has been submitted — server-side code is used to validate the data before it is put into the database, and if it is wrong a response is sent back to the client to tell the user what went wrong. Server-side validation is not as user-friendly as client-side validation, as it requires a round trip to the server, but it is essential — it is your application's last line of defense against bad data. All popular server-side frameworks have features for validating and sanitizing data (making it safe).

In the real world, developers tend to use a combination of client-side and server-side validation, to be on the safe side.

Using built-in form validation

One of the features of HTML5 is the ability to validate most user data without relying on scripts. This is done using validation attributes on form elements, which allow you to specify rules for a form input like whether a value needs to be filled in, the minimum and maximum length of the data, whether it needs to be a number, an email address, etc., and a pattern that it must match. If the entered data follows all those rules, it is considered valid; if not, it is considered invalid.

When an element is valid:

- The element matches the

:validpseudo-class; this will let you apply a specific style to valid elements. - If the user tries to send the data, the browser will submit the form, provided there is nothing else stopping it from doing so (like JavaScript, for example).

When an element is invalid:

- The element matches the

:invalidCSS pseudo-class; this will let you apply a specific style to invalid elements. - If the user tries to send the data, the browser will block the form and display an error message.

Validation constraints on input elements — starting simple

In this section we'll look at some of the different HTML5 features that can be used to validate <input> elements.

Let's start with a simple example — an input that allows you to choose your favourite fruit out of a choice of banana or cherry. This involves a simple text <input> with matching label, and a submit <button>. You can find the source code on GitHub as fruit-start.html, and a live example below:

Hidden code

<form> <label for="choose">Would you prefer a banana or cherry?</label> <input id="choose" name="i_like"> <button>Submit</button> </form>

input:invalid {

border: 2px dashed red;

}

input:valid {

border: 2px solid black;

}

To begin with, make a copy of fruit-start.html in a new directory on your hard drive.

The required attribute

The simplest HTML5 validation feature to use is the required attribute — if you want to make an input mandatory, you can mark the element using this attribute. When this attribute is set, the form won't submit (and will display an error message) when the input is empty (the input will also be considered invalid).

Add a required attribute to your input, as shown below:

<form> <label for="choose">Would you prefer a banana or cherry?</label> <input id="choose" name="i_like" required> <button>Submit</button> </form>

Also take note of the CSS included in the example file:

input:invalid {

border: 2px dashed red;

}

input:valid {

border: 2px solid black;

}

This causes the input to have a bright red dashed border when it is invalid, and a more subtle black border when valid. Try out the new behaviour in the example below:

Validating against a regular expression

Another very common validation feature is the pattern attribute, which expects a Regular Expression as its value. A regular expression (regex) is a pattern that can be used to match character combinations in text strings, so they are ideal for form validation (as well as variety of other uses in JavaScript). Regexs are quite complex and we do not intend to teach you them exhaustively in this article.

Below are some examples to give you a basic idea of how they work:

a— matches one character that is a (not b, not aa, etc.)abc— matchesa, followed byb, followed byc.a*— matches the character a, zero or more times (+matches a character one or more times).[^a]— matches one character that is not a.a|b— matches one character that is a or b.[abc]— matches one character that is a, b, or c.[^abc]— matches one character that is not a, b, or c.[a-z]— matches any character in the range a–z, lower case only (you can use[A-z]for lower and upper case, and[A-Z]for upper case only).a.c— matches a, followed by any character, followed by c.a{5}— matches a, 5 times.a{5,7}— matches a, 5 to 7 times, but no less or more.

You can use numbers and other characters in these expressions too, e.g.:

[ |-]— matches a space or a dash.- [0-9] — matches any number in the range 0 to 9.

You can combine these in pretty much any way you want, specifying different parts one after the other:

[Ll].*k— A single character that is an upper or lowercase L, followed by zero or more characters of any type, followed by a single lowercase k.[A-Z][A-z|-|']+— A single upper case character followed by one or more characters that are an upper or lower case letter, or a dash, or an apostrophe, or a space. This could be used to validate the city/town names of English-speaking countries, which need to start with a capital letter, but don't contain any other characters (you could add exceptions as you find them). Examples from the UK include Manchester, Ashton-under-lyne, and Bishop's Stortford. You could write the last block as[A-z-' ]+(without the pipe characters), but it isn't as easy to read.[0-9]{3}[ |-][0-9]{3}[ |-][0-9]{4}— A simple match for a US domestic phone number — three numbers 0-9, followed by a space or a dash, followed three numbers 0-9, followed by a space or a dash, followed by four numbers 0-9. You might have to make this more complex, as some people write their area code in parentheses, but it works for a simple demonstration.

Anyway, let's implement an example — update your HTML to add a pattern attribute, like so:

<form> <label for="choose">Would you prefer a banana or a cherry?</label> <input id="choose" name="i_like" required pattern="banana|cherry"> <button>Submit</button> </form>

input:invalid {

border: 2px dashed red;

}

input:valid {

border: 2px solid black;

}

In this example, the <input> element accepts one of two possible values: the string "banana" or the string "cherry".

At this point, try changing the value inside the pattern attribute to equal some of the examples you saw earlier, and look at how that affects the values you can enter to make the input value valid. Try writing some of your own, and see how you get on! Try to make them fruit-related where possible, so you example make sense!

Note: Some <input> element types do not need a pattern attribute to be validated. Specifying the email type for example validates the inputted value against a regular expression matching a well-formed email address (or a comma-separated list of email addresses if it has the multiple attribute). As a further example, fields with the url type automatically require a properly-formed URL.

Note: The <textarea> element does not support the pattern attribute.

Constraining the length of your entries

All text fields (<input> or <textarea>) can be constrained in size using the maxlength attribute. A field is invalid if its value is longer than the maxlength attribute's value. Browsers often don't let the user type a longer value than expected into text fields anyway, but it is useful to have this fine-grained control available.

For number fields (i.e. <input type="number">), the min and max attributes also provide a validation constraint. If the field's value is lower than the min attribute or higher than the max attribute, the field will be invalid.

Let's look at another example. Create a new copy of fruit-start.html file.

Now delete the contents of the <body> element, and replace it with the following:

<form>

<p>

<label for="n1">How old are you?</label>

<input type="number" id="n1" name="age" pattern="[0-9]+">

</p>

<p>

<label for="t3">Leave a short message</label>

<textarea id="t3" name="msg" rows="5"></textarea>

</p>

<p>

<button>Submit</button>

</p>

</form>

GOT HERE; EXPLAIN ADDITIONS.

Note: <input type="number"> (and other types, like range) can also take a step attribute, which specifies what increment the value will go up or down by when the input controls are used (like the up and down number buttons).

Other validation constraints

Here is a full example :

<form>

<p>

<fieldset>

<legend>Title<abbr title="This field is mandatory">*</abbr></legend>

<input type="radio" required name="title" id="r1" value="Mr"><label for="r1">Mr.</label>

<input type="radio" required name="title" id="r2" value="Ms"><label for="r2">Ms.</label>

</fieldset>

</p>

<p>

<label for="n1">How old are you?</label>

<!-- The pattern attribute can act as a fallback for browsers which

don't implement the number input type but support the pattern attribute.

Please note that browsers that support the pattern attribute will make it

fail silently when used with a number field.

Its usage here acts only as a fallback -->

<input type="number" min="12" max="120" step="1" id="n1" name="age"

pattern="\d+">

</p>

<p>

<label for="t1">What's your favorite fruit?<abbr title="This field is mandatory">*</abbr></label>

<input type="text" id="t1" name="fruit" list="l1" required

pattern="[Bb]anana|[Cc]herry|[Aa]pple|[Ss]trawberry|[Ll]emon|[Oo]range">

<datalist id="l1">

<option>Banana</option>

<option>Cherry</option>

<option>Apple</option>

<option>Strawberry</option>

<option>Lemon</option>

<option>Orange</option>

</datalist>

</p>

<p>

<label for="t2">What's your e-mail?</label>

<input type="email" id="t2" name="email">

</p>

<p>

<label for="t3">Leave a short message</label>

<textarea id="t3" name="msg" maxlength="140" rows="5"></textarea>

</p>

<p>

<button>Submit</button>

</p>

</form>

body {

font: 1em sans-serif;

padding: 0;

margin : 0;

}

form {

max-width: 200px;

margin: 0;

padding: 0 5px;

}

p > label {

display: block;

}

input[type=text],

input[type=email],

input[type=number],

textarea,

fieldset {

/* required to properly style form

elements on WebKit based browsers */

-webkit-appearance: none;

width : 100%;

border: 1px solid #333;

margin: 0;

font-family: inherit;

font-size: 90%;

-moz-box-sizing: border-box;

box-sizing: border-box;

}

input:invalid {

box-shadow: 0 0 5px 1px red;

}

input:focus:invalid {

outline: none;

}

Customized error messages

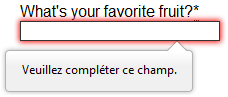

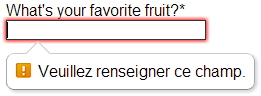

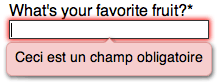

As we saw in all of the above examples, each time the user tries to send an invalid form, the browser displays an error message. The way this message is displayed depends on the browser.

These automated messages have two drawbacks:

- There is no standard way to change their look and feel with CSS.

- They depend on the browser locale, which means that you can have a page in one language but an error message displayed in another language.

| Browser | Rendering |

|---|---|

| Firefox 17 (Windows 7) |  |

| Chrome 22 (Windows 7) |  |

| Opera 12.10 (Mac OSX) |  |

To customize the appearance and text of these messages, you must use JavaScript; there is no way to do it using just HTML and CSS.

HTML5 provides the constraint validation API to check and customize the state of a form element. Among other things, it's possible to change the text of the error message. Let's see a quick example:

<form> <label for="mail">I would like you to provide me an e-mail</label> <input type="email" id="mail" name="mail"> <button>Submit</button> </form>

In JavaScript, you call the setCustomValidity() method:

var email = document.getElementById("mail");

email.addEventListener("input", function (event) {

if (email.validity.typeMismatch) {

email.setCustomValidity("I expect an e-mail, darling!");

} else {

email.setCustomValidity("");

}

});

Validating forms using JavaScript

If you want to take control over the look and feel of native error message, or if you want to deal with browsers that do not support HTML5 forms validation, there is no way but to use JavaScript.

The HTML5 constraint validation API

More and more browsers now support the constraint validation API, and it's becoming reliable. This API consists of a set of methods and properties available on each form element.

Constraint validation API properties

| Property | Description |

|---|---|

validationMessage |

A localized message describing the validation constraints that the control does not satisfy (if any), or the empty string if the control is not a candidate for constraint validation (willValidate is false), or the element's value satisfies its constraints. |

validity |

A ValidityState object describing the validity state of the element. |

validity.customError |

Returns true if the element has a custom error; false otherwise. |

validity.patternMismatch |

Returns true if the element's value doesn't match the provided pattern; false otherwise.If it returns true, the element will match the :invalid CSS pseudo-class. |

validity.rangeOverflow |

Returns true if the element's value is higher than the provided maximum; false otherwise.If it returns true, the element will match the :invalid and :out-of-range and CSS pseudo-class. |

validity.rangeUnderflow |

Returns true if the element's value is lower than the provided minimum; false otherwise.If it returns true, the element will match the :invalid and :out-of-range CSS pseudo-class. |

validity.stepMismatch |

Returns true if the element's value doesn't fit the rules provided by the step attribute; otherwise false .If it returns true, the element will match the :invalid and :out-of-range CSS pseudo-class. |

validity.tooLong |

Returns true if the element's value is longer than the provided maximum length; else it wil be false If it returns true, the element will match the :invalid and :out-of-range CSS pseudo-class. |

validity.typeMismatch |

Returns true if the element's value is not in the correct syntax;otherwise false. If it returns true, the element will match the :invalid css pseudo-class. |

validity.valid |

Returns true if the element's value has no validity problems; false otherwise. If it returns true, the element will match the :valid css pseudo-class; the :invalid CSS pseudo-class otherwise. |

validity.valueMissing |

Returns true if the element has no value but is a required field; false otherwise. If it returns true, the element will match the :invalid CSS pseudo-class. |

willValidate |

Returns true if the element will be validated when the form is submitted; false otherwise. |

Constraint validation API methods

| Method | Description |

|---|---|

checkValidity() |

Returns true if the element's value has no validity problems; false otherwise. If the element is invalid, this method also causes an invalid event at the element. |

setCustomValidity(message) |

Adds a custom error message to the element; if you set a custom error message, the element is considered to be invalid, and the specified error is displayed. This lets you use JavaScript code to establish a validation failure other than those offered by the standard constraint validation API. The message is shown to the user when reporting the problem. If the argument is the empty string, the custom error is cleared. |

For legacy browsers, it's possible to use a polyfill such as Hyperform to compensate for the lack of support for the constraint validation API. Since you're already using JavaScript, using a polyfill isn't an added burden to your Web site or Web application's design or implementation.

Example using the constraint validation API

Let's see how to use this API to build custom error messages. First, the HTML:

<form novalidate>

<p>

<label for="mail">

<span>Please enter an email address:</span>

<input type="email" id="mail" name="mail">

<span class="error" aria-live="polite"></span>

</label>

</p>

<button>Submit</button>

</form>

This simple form uses the novalidate attribute to turn off the browser's automatic validation; this lets our script take control over validation. However, this doesn't disable support for the constraint validation API nor the application of the CSS pseudo-class :valid, :invalid, :in-range and :out-of-range classes. That means that even though the browser doesn't automatically check the validity of the form before sending its data, you can still do it yourself and style the form accordingly.

The aria-live attribute makes sure that our custom error message will be presented to everyone, including those using assistive technologies such as screen readers.

CSS

This CSS styles our form and the error output to look more attractive.

/* This is just to make the example nicer */

body {

font: 1em sans-serif;

padding: 0;

margin : 0;

}

form {

max-width: 200px;

}

p * {

display: block;

}

input[type=email]{

-webkit-appearance: none;

width: 100%;

border: 1px solid #333;

margin: 0;

font-family: inherit;

font-size: 90%;

-moz-box-sizing: border-box;

box-sizing: border-box;

}

/* This is our style for the invalid fields */

input:invalid{

border-color: #900;

background-color: #FDD;

}

input:focus:invalid {

outline: none;

}

/* This is the style of our error messages */

.error {

width : 100%;

padding: 0;

font-size: 80%;

color: white;

background-color: #900;

border-radius: 0 0 5px 5px;

-moz-box-sizing: border-box;

box-sizing: border-box;

}

.error.active {

padding: 0.3em;

}

JavaScript

The following JavaScript code handles the custom error validation.

// There are many ways to pick a DOM node; here we get the form itself and the email

// input box, as well as the span element into which we will place the error message.

var form = document.getElementsByTagName('form')[0];

var email = document.getElementById('mail');

var error = document.querySelector('.error');

email.addEventListener("input", function (event) {

// Each time the user types something, we check if the

// email field is valid.

if (email.validity.valid) {

// In case there is an error message visible, if the field

// is valid, we remove the error message.

error.innerHTML = ""; // Reset the content of the message

error.className = "error"; // Reset the visual state of the message

}

}, false);

form.addEventListener("submit", function (event) {

// Each time the user tries to send the data, we check

// if the email field is valid.

if (!email.validity.valid) {

// If the field is not valid, we display a custom

// error message.

error.innerHTML = "I expect an e-mail, darling!";

error.className = "error active";

// And we prevent the form from being sent by canceling the event

event.preventDefault();

}

}, false);

Here is the live result:

The constraint validation API gives you a powerful tool to handle form validation, letting you have enormous control over the user interface above and beyond what you can do just with HTML and CSS alone.

Validating forms without a built-in API

Sometimes, such as with legacy browsers or custom widgets, you will not be able to (or will not want to) use the constraint validation API. In that case, you're still able to use JavaScript to validate your form. Validating a form is more a question of user interface than real data validation.

To validate a form, you have to ask yourself a few questions:

- What kind of validation should I perform?

- You need to determine how to validate your data: string operations, type conversion, regular expressions, etc. It's up to you. Just remember that form data is always text and is always provided to your script as strings.

- What should I do if the form does not validate?

- This is clearly a UI matter. You have to decide how the form will behave: Does the form send the data anyway? Should you highlight the fields which are in error? Should you display error messages?

- How can I help the user to correct invalid data?

- In order to reduce the user's frustration, it's very important to provide as much helpful information as possible in order to guide them in correcting their inputs. You should offer up-front suggestions so they know what's expected, as well as clear error messages.

If you want to dig into form validation UI requirements, there are some useful articles you should read:

- SmashingMagazine: Form-Field Validation: The Errors-Only Approach

- SmashingMagazine: Web Form Validation: Best Practices and Tutorials

- Six Revision: Best Practices for Hints and Validation in Web Forms

- A List Apart: Inline Validation in Web Forms

Example that doesn't use the constraint validation API

In order to illustrate this, let's rebuild the previous example so that it works with legacy browsers:

<form>

<p>

<label for="mail">

<span>Please enter an email address:</span>

<input type="text" class="mail" id="mail" name="mail">

<span class="error" aria-live="polite"></span>

</label>

<p>

<!-- Some legacy browsers need to have the `type` attribute

explicitly set to `submit` on the `button`element -->

<button type="submit">Submit</button>

</form>

As you can see, the HTML is almost the same; we just removed the HTML5 parts. Note that ARIA is an independent specification that's not specifically related to HTML5, so it's still here.

CSS

Similarly, the CSS doesn't need to change very much; we just turn the :invalid pseudo-class into a real class and avoid using the attribute selector that does not work on Internet Explorer 6.

/* This is just to make the example nicer */

body {

font: 1em sans-serif;

padding: 0;

margin : 0;

}

form {

max-width: 200px;

}

p * {

display: block;

}

input.mail {

-webkit-appearance: none;

width: 100%;

border: 1px solid #333;

margin: 0;

font-family: inherit;

font-size: 90%;

-moz-box-sizing: border-box;

box-sizing: border-box;

}

/* This is our style for the invalid fields */

input.invalid{

border-color: #900;

background-color: #FDD;

}

input:focus.invalid {

outline: none;

}

/* This is the style of our error messages */

.error {

width : 100%;

padding: 0;

font-size: 80%;

color: white;

background-color: #900;

border-radius: 0 0 5px 5px;

-moz-box-sizing: border-box;

box-sizing: border-box;

}

.error.active {

padding: 0.3em;

}

JavaScript

The big changes are in the JavaScript code, which needs to do much more of the heavy lifting.

// There are fewer ways to pick a DOM node with legacy browsers

var form = document.getElementsByTagName('form')[0];

var email = document.getElementById('mail');

// The following is a trick to reach the next sibling Element node in the DOM

// This is dangerous because you can easily build an infinite loop.

// In modern browsers, you should prefer using element.nextElementSibling

var error = email;

while ((error = error.nextSibling).nodeType != 1);

// As per the HTML5 Specification

var emailRegExp = /^[a-zA-Z0-9.!#$%&'*+/=?^_`{|}~-]+@[a-zA-Z0-9-]+(?:\.[a-zA-Z0-9-]+)*$/;

// Many legacy browsers do not support the addEventListener method.

// Here is a simple way to handle this; it's far from the only one.

function addEvent(element, event, callback) {

var previousEventCallBack = element["on"+event];

element["on"+event] = function (e) {

var output = callback(e);

// A callback that returns `false` stops the callback chain

// and interrupts the execution of the event callback.

if (output === false) return false;

if (typeof previousEventCallBack === 'function') {

output = previousEventCallBack(e);

if(output === false) return false;

}

}

};

// Now we can rebuild our validation constraint

// Because we do not rely on CSS pseudo-class, we have to

// explicitly set the valid/invalid class on our email field

addEvent(window, "load", function () {

// Here, we test if the field is empty (remember, the field is not required)

// If it is not, we check if its content is a well-formed e-mail address.

var test = email.value.length === 0 || emailRegExp.test(email.value);

email.className = test ? "valid" : "invalid";

});

// This defines what happens when the user types in the field

addEvent(email, "input", function () {

var test = email.value.length === 0 || emailRegExp.test(email.value);

if (test) {

email.className = "valid";

error.innerHTML = "";

error.className = "error";

} else {

email.className = "invalid";

}

});

// This defines what happens when the user tries to submit the data

addEvent(form, "submit", function () {

var test = email.value.length === 0 || emailRegExp.test(email.value);

if (!test) {

email.className = "invalid";

error.innerHTML = "I expect an e-mail, darling!";

error.className = "error active";

// Some legacy browsers do not support the event.preventDefault() method

return false;

} else {

email.className = "valid";

error.innerHTML = "";

error.className = "error";

}

});

The result looks like this:

As you can see, it's not that hard to build a validation system on your own. The difficult part is to make it generic enough to use it both cross-platform and on any form you might create. There are many libraries available to perform form validation; you shouldn't hesitate to use them. Here are a few examples:

- Standalone library

- jQuery plug-in:

Remote validation

In some cases it can be useful to perform some remote validation. This kind of validation is necessary when the data entered by the user is tied to additional data stored on the server side of your application. One use case for this is registration forms, where you ask for a user name. To avoid duplication, it's smarter to perform an AJAX request to check the availability of the user name rather than asking the user to send the data, then send back the form with an error.

Performing such a validation requires taking a few precautions:

- It requires exposing an API and some data publicly; be sure it is not sensitive data.

- Network lag requires performing asynchronous validation. This requires some UI work in order to be sure that the user will not be blocked if the validation is not performed properly.

Conclusion

Form validation does not require complex JavaScript, but it does require thinking carefully about the user. Always remember to help your user to correct the data he provides. To that end, be sure to:

- Display explicit error messages.

- Be permissive about the input format.

- Point out exactly where the error occurs (especially on large forms).