First, let’s start IPython. It is a most excellent enhancement to the standard Python prompt, and it ties in especially well with Matplotlib. Start IPython either at a shell, or the IPython Notebook now.

With IPython started, we now need to connect to a GUI event loop. This tells IPython where (and how) to display plots. To connect to a GUI loop, execute the %matplotlib magic at your IPython prompt. There’s more detail on exactly what this does at IPython’s documentation on GUI event loops.

If you’re using IPython Notebook, the same commands are available, but people commonly use a specific argument to the %matplotlib magic:

In [1]: %matplotlib inline

This turns on inline plotting, where plot graphics will appear in your notebook. This has important implications for interactivity. For inline plotting, commands in cells below the cell that outputs a plot will not affect the plot. For example, changing the color map is not possible from cells below the cell that creates a plot. However, for other backends, such as qt4, that open a separate window, cells below those that create the plot will change the plot - it is a live object in memory.

This tutorial will use matplotlib’s imperative-style plotting interface, pyplot. This interface maintains global state, and is very useful for quickly and easily experimenting with various plot settings. The alternative is the object-oriented interface, which is also very powerful, and generally more suitable for large application development. If you’d like to learn about the object-oriented interface, a great place to start is our FAQ on usage. For now, let’s get on with the imperative-style approach:

In [2]: import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

In [3]: import matplotlib.image as mpimg

In [4]: import numpy as np

Loading image data is supported by the Pillow library. Natively, matplotlib only supports PNG images. The commands shown below fall back on Pillow if the native read fails.

The image used in this example is a PNG file, but keep that Pillow requirement in mind for your own data.

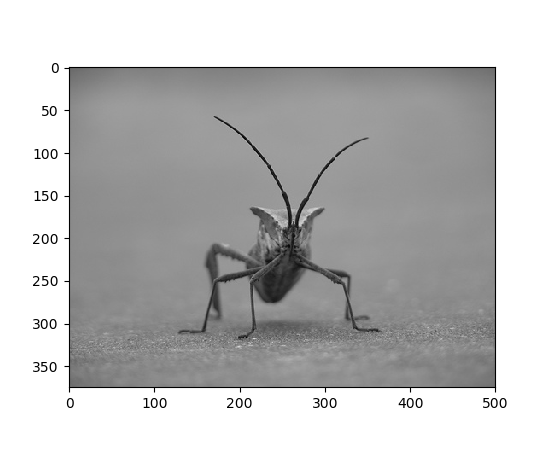

Here’s the image we’re going to play with:

It’s a 24-bit RGB PNG image (8 bits for each of R, G, B). Depending on where you get your data, the other kinds of image that you’ll most likely encounter are RGBA images, which allow for transparency, or single-channel grayscale (luminosity) images. You can right click on it and choose “Save image as” to download it to your computer for the rest of this tutorial.

And here we go...

In [5]: img=mpimg.imread('stinkbug.png')

Out[5]:

array([[[ 0.40784314, 0.40784314, 0.40784314],

[ 0.40784314, 0.40784314, 0.40784314],

[ 0.40784314, 0.40784314, 0.40784314],

...,

[ 0.42745098, 0.42745098, 0.42745098],

[ 0.42745098, 0.42745098, 0.42745098],

[ 0.42745098, 0.42745098, 0.42745098]],

...,

[[ 0.44313726, 0.44313726, 0.44313726],

[ 0.4509804 , 0.4509804 , 0.4509804 ],

[ 0.4509804 , 0.4509804 , 0.4509804 ],

...,

[ 0.44705883, 0.44705883, 0.44705883],

[ 0.44705883, 0.44705883, 0.44705883],

[ 0.44313726, 0.44313726, 0.44313726]]], dtype=float32)

Note the dtype there - float32. Matplotlib has rescaled the 8 bit data from each channel to floating point data between 0.0 and 1.0. As a side note, the only datatype that Pillow can work with is uint8. Matplotlib plotting can handle float32 and uint8, but image reading/writing for any format other than PNG is limited to uint8 data. Why 8 bits? Most displays can only render 8 bits per channel worth of color gradation. Why can they only render 8 bits/channel? Because that’s about all the human eye can see. More here (from a photography standpoint): Luminous Landscape bit depth tutorial.

Each inner list represents a pixel. Here, with an RGB image, there are 3 values. Since it’s a black and white image, R, G, and B are all similar. An RGBA (where A is alpha, or transparency), has 4 values per inner list, and a simple luminance image just has one value (and is thus only a 2-D array, not a 3-D array). For RGB and RGBA images, matplotlib supports float32 and uint8 data types. For grayscale, matplotlib supports only float32. If your array data does not meet one of these descriptions, you need to rescale it.

So, you have your data in a numpy array (either by importing it, or by

generating it). Let’s render it. In Matplotlib, this is performed

using the imshow() function. Here we’ll grab

the plot object. This object gives you an easy way to manipulate the

plot from the prompt.

In [6]: imgplot = plt.imshow(img)

(Source code, png, pdf)

You can also plot any numpy array.

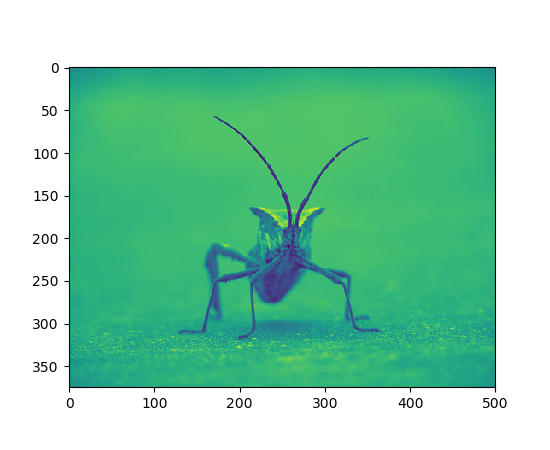

Pseudocolor can be a useful tool for enhancing contrast and visualizing your data more easily. This is especially useful when making presentations of your data using projectors - their contrast is typically quite poor.

Pseudocolor is only relevant to single-channel, grayscale, luminosity images. We currently have an RGB image. Since R, G, and B are all similar (see for yourself above or in your data), we can just pick one channel of our data:

In [7]: lum_img = img[:,:,0]

This is array slicing. You can read more in the Numpy tutorial.

In [8]: plt.imshow(lum_img)

(Source code, png, pdf)

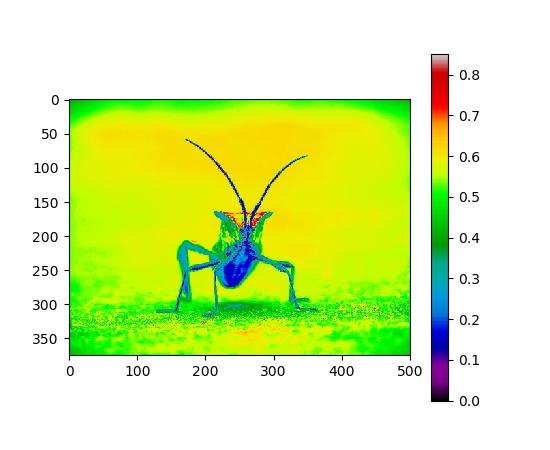

Now, with a luminosity (2D, no color) image, the default colormap (aka lookup table, LUT), is applied. The default is called jet. There are plenty of others to choose from.

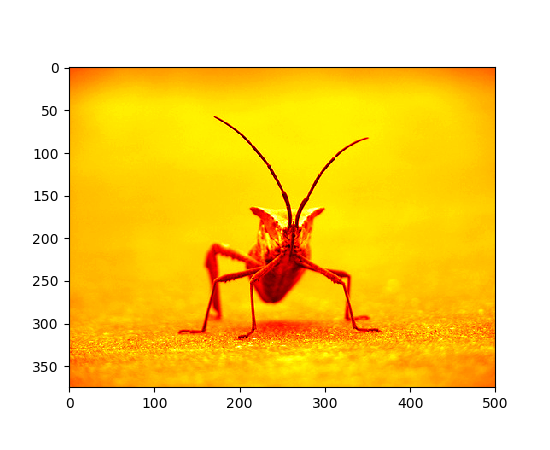

In [9]: plt.imshow(lum_img, cmap="hot")

(Source code, png, pdf)

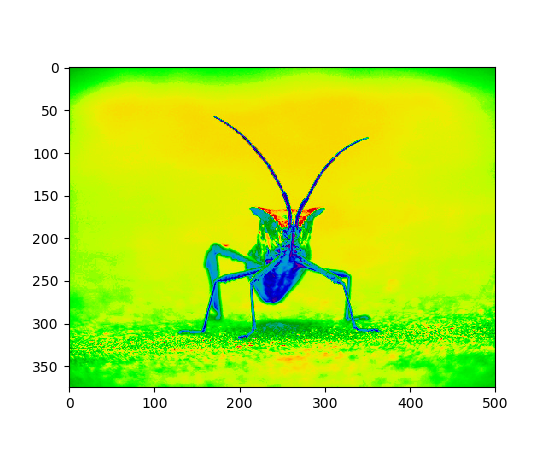

Note that you can also change colormaps on existing plot objects using the

set_cmap() method:

In [10]: imgplot = plt.imshow(lum_img)

In [11]: imgplot.set_cmap('nipy_spectral')

(Source code, png, pdf)

Note

However, remember that in the IPython notebook with the inline backend, you can’t make changes to plots that have already been rendered. If you create imgplot here in one cell, you cannot call set_cmap() on it in a later cell and expect the earlier plot to change. Make sure that you enter these commands together in one cell. plt commands will not change plots from earlier cells.

There are many other colormap schemes available. See the list and images of the colormaps.

It’s helpful to have an idea of what value a color represents. We can do that by adding color bars.

In [12]: imgplot = plt.imshow(lum_img)

In [13]: plt.colorbar()

(Source code, png, pdf)

This adds a colorbar to your existing figure. This won’t automatically change if you change you switch to a different colormap - you have to re-create your plot, and add in the colorbar again.

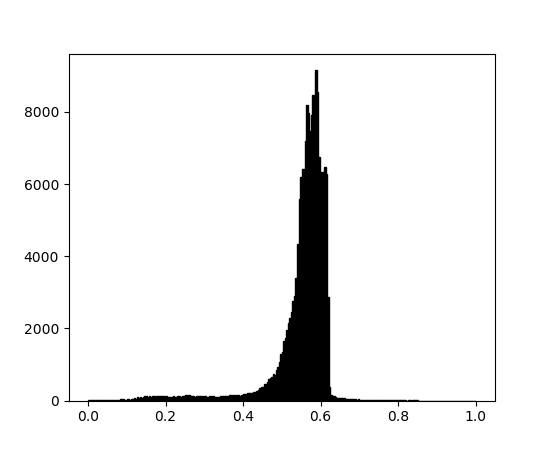

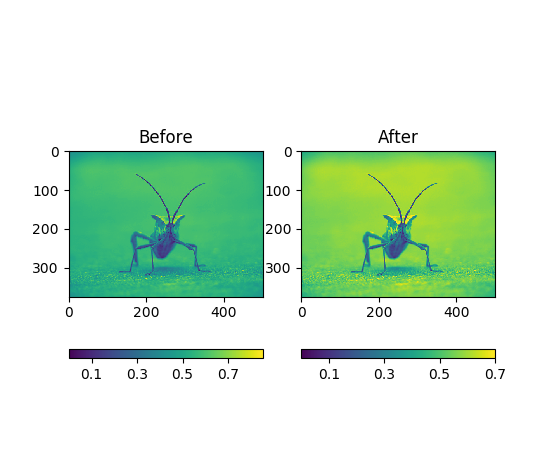

Sometimes you want to enhance the contrast in your image, or expand

the contrast in a particular region while sacrificing the detail in

colors that don’t vary much, or don’t matter. A good tool to find

interesting regions is the histogram. To create a histogram of our

image data, we use the hist() function.

In [14]: plt.hist(lum_img.ravel(), bins=256, range=(0.0, 1.0), fc='k', ec='k')

(Source code, png, pdf)

Most often, the “interesting” part of the image is around the peak,

and you can get extra contrast by clipping the regions above and/or

below the peak. In our histogram, it looks like there’s not much

useful information in the high end (not many white things in the

image). Let’s adjust the upper limit, so that we effectively “zoom in

on” part of the histogram. We do this by passing the clim argument to

imshow. You could also do this by calling the

set_clim() method of the image plot

object, but make sure that you do so in the same cell as your plot

command when working with the IPython Notebook - it will not change

plots from earlier cells.

In [15]: imgplot = plt.imshow(lum_img, clim=(0.0, 0.7))

(Source code, png, pdf)

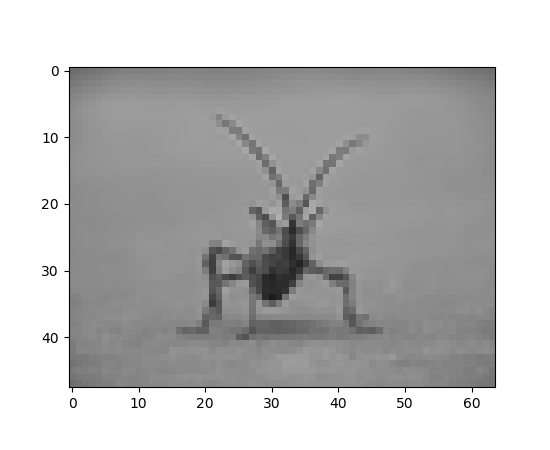

Interpolation calculates what the color or value of a pixel “should” be, according to different mathematical schemes. One common place that this happens is when you resize an image. The number of pixels change, but you want the same information. Since pixels are discrete, there’s missing space. Interpolation is how you fill that space. This is why your images sometimes come out looking pixelated when you blow them up. The effect is more pronounced when the difference between the original image and the expanded image is greater. Let’s take our image and shrink it. We’re effectively discarding pixels, only keeping a select few. Now when we plot it, that data gets blown up to the size on your screen. The old pixels aren’t there anymore, and the computer has to draw in pixels to fill that space.

We’ll use the Pillow library that we used to load the image also to resize the image.

In [16]: from PIL import Image

In [17]: img = Image.open('../_static/stinkbug.png')

In [18]: img.thumbnail((64, 64), Image.ANTIALIAS) # resizes image in-place

In [19]: imgplot = plt.imshow(img)

(Source code, png, pdf)

Here we have the default interpolation, bilinear, since we did not

give imshow() any interpolation argument.

Let’s try some others:

In [20]: imgplot = plt.imshow(img, interpolation="nearest")

(Source code, png, pdf)

In [21]: imgplot = plt.imshow(img, interpolation="bicubic")

(Source code, png, pdf)

Bicubic interpolation is often used when blowing up photos - people tend to prefer blurry over pixelated.